Pulse Check: The unexpected gift of long COVID. Could new research treat chronic fatigue syndromes and cure cancer?

Brain fog, fatigue, nervous system abnormalities, headaches, and body aches. It's time these complaints were taken seriously. Psychosomatic? Novel research on long-COVID gives us another explanation.

If you find this piece worthwhile, consider the Go Fund Me that’s funding Jake’s ongoing cancer care.

Let’s rewind history for a moment to see how we got to taking mysterious clusters of weird patient complaints seriously. For years, patients with symptoms like brain fog, nervous system problems, and fatigue have been grouped together under a blanket diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) / myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME—“ME” is the same thing as CFS, but it uses confusing, Latinate words and so makes doctors sound mysterious and powerful, like wizards), psychosomatic syndromes (which approximately means “we think it’s all in your head”), or some other “we don’t know” diagnoses.

Maybe someone you know has or has had something wrong with them, something that doctors haven’t really be able to diagnose, or that doctors have “diagnosed” with vague catch-all terms like “CFS.” I’ve been on the doctor side of telling patients that I don’t know what’s wrong with them and can’t figure it out from the ER. I’ve seen the frustration patients justifiably feel at that frustrating, but also honest, response. Sometimes we don’t know, and neither does anyone else, not really, because the science hasn’t caught up. As a patient, I’ve also been on the receiving end of “I don’t know,” so I get how demoralizing it is to feel like I’m not being heard—and to so badly want a diagnosis and solution.

So what’s going on? And what progress is being made? It took a catastrophe to begin taking mystery symptoms and clusters seriously. I know that catastrophe well, because I was literally in the middle of it. In March and April 2020, I was working in Brooklyn’s Brookdale hospital ER. Brookdale was, charitably, under-resourced even in normal times, and NYC was then being crushed by COVID: Every zone in the ER was hot, patients were on beds, chairs, and overflowing onto the floor.

Many patients would sit around remaining IV poles, so that multiple bags of fluids and medications could be hung at once. We’d run out of oxygen tanks, and then had to start making brutal, impossible decisions about who got a ventilator spot when one became available. I was accepting back-alley drop-exchanges of personal protective equipment (PPE) and spending my paycheck on grossly price-inflated, possibly fake, masks.

Strangers would cross the street when they saw me in scrubs, afraid the viral miasma around healthcare workers would jump from us to them (these were the days of wiping down grocery bags and mail, and before we knew that COVID is extremely hard to spread outdoors), even as people hung out of their windows at 7 p.m. banging pots and pans for “healthcare heroes.” I felt less heroic and more “I’m desperately trying to stay alive and do this, day by day.”

Tales of colleagues who’ d succumbed to COVID or were extremely sick from it got passed around. Exhausted, burned out, and all of us with at least one dead colleague, and even more dead patients in the refrigerated morgue trucks parked in the back of the hospital, we found that we either slept like the dead who haunted us during the day, or that our dreams were filled with them.

Back then, if I’d read the words “the gift of COVID,” I’d assume someone was sarcastically talking about the PTSD symptoms healthcare professionals were developing.

Instead, four years into a pandemic, I can see now that there are two major, and majorly unexpected, silver linings:

· Difficult to pin-down, chronic, life-altering symptoms such as severe fatigue and cognitive difficulties that were previously dismissed as psychosomatic or otherwise misunderstood are getting attention and being reconceptualized as physiologic processes, thanks to of the sheer number of long-COVID sufferers.

· Fast, successful development of COVID mRNA vaccines are paving the way for future mRNA vaccines that could prevent cancer, Alzheimers and multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as accelerating cancer mRNA research, which’ll radically alter cancer treatment—and change my own life (we should’ve had mRNA vaccines much sooner, but that’s discussed at the link and I don’t want to turn this essay into a rant about complacency and its victims, like my husband).

Part 1 of this is about taking difficult to pin down, chronic, life-altering symptoms more seriously. We’ll look at the new science of long-COVID and the connections between long-COVID and other “Post-Acute-Infection-Syndromes (PAISes), Part 2 is about the potential role of mRNA vaccines in preventing some of these challenges and even treating them.

Long COVID makes scientists ask: what other chronic problems are infectious pathogens causing, and are they causing it in the same way as COVID?

The WHO characterizes “long COVID” as “probable or confirmed SARS-2 infections with new or persisting symptoms 3 months after infection that cannot be explained by alternative causes.” Common long COVID symptoms are neurologic symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive dysfunction or “brain fog,” headaches and dysautonomia (a fancy word for “autonomic nervous system not working properly”), cardiovascular symptoms like abnormal heart rhythms and cardiac inflammation, respiratory symptoms like shortness of breath and diminished lung capacity, and even metabolic symptoms such as increased cholesterol and LDH and diabetes. Swing by Eric Topol’s Substack or read his full paper in Science for a comprehensive description.

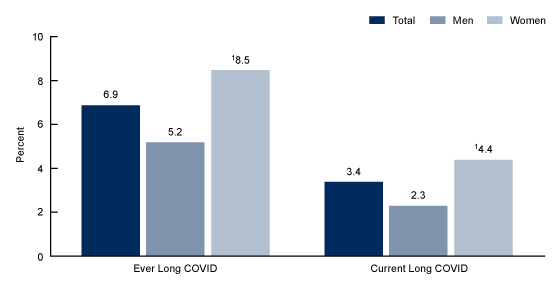

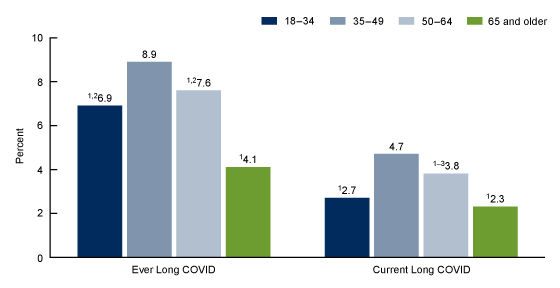

Long COVID affects ~6.9% of adults. Women are more likely than men to develop long COVID (8.5% v 5.2%). Adults ages 35-49—an age group that is likely both caretaking for children and elderly parents, as well working and therefore vital to the economy—are more likely to get long COVID, leading to a sustained, negative, economic impact.

Percentage of adults who ever had Long COVID or currently have Long COVID, by sex

Percentage of adults who ever had Long COVID or currently have Long COVID, by age group: United States, 2022

The numbers are likely to be higher now as COVID is both endemic and continuing to infect people at pandemic-levels. Re-infection is an independent risk factor for long COVID. As I mentioned at the start of this essay, although long COVID is obviously bad, similar panoplies of symptoms have plagued patients—especially female patients—before.

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) / myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)1 is, I think, likely a catch-all diagnosis that includes a vast number of other Post-Acute-Infectious Syndromes (PAISes), which are any long-term chronic symptoms triggered by an initial infection. PAISes are well-documented across viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections, and they’re frequently underrecognized by doctors and scientists, in part because they’re often difficult or impossible to test for. Broken bone? I’ll see it on an x-ray. Too much partying last week? A urine test will show me that you’ve got gonorrhea and need an antibiotic. But pain? Brain fog? Excessive tiredness? I don’t have any reliable tests in clinic for them.

Even though PAISes and chronic symptoms are underrecognized, they’re not necessarily rare: syndromes following the cessation of acute symptoms have been noted for Ebola, Chickingunya, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), Lyme disease, and, of course, COVID. But a lack of definitive testing, due to a lack of adequate biomarkers (measurable chemicals in the blood that are associated with a disease) to test for, along with difficulty identifying a triggering infection (a triggering infection may have been so minor that the PAIS is far worse than the mild illness preceding it) are all challenges to diagnoses. I wouldn’t be surprised to find that most pathogens are capable of triggering a PAIS of varying degrees, or that PAISes are responsible for a larger number of difficult-to-diagnose symptoms than previously imagined.

You might’ve had a PAIS. Ever had a cold or flu you’ve been slow to recover from? “Cold or flu” is often just a generic term for “some kind of virus or bacteria.” If you’ve taken weeks or even months longer to recover than you think you should have, then you’ve likely had PAIS. But, as with so many things, PAISes can vary in intensity. If Joe is more tired than usual for a couple weeks, and sleeps more than he usually does, but then feels better, that’s one thing. If Jane spends years with debilitating fatigue and body aches that affects her ability to hold a job and live a normal life, that’s another.

For too long, doctors have found it easy to ignore PAISes or to slap a diagnosis on it like “CFS / ME,” then move on to the next patient. But PAISes are characterized by a similar set of core symptoms as long-COVID: fatigue, cognitive dysfunction or “brain fog”, respiratory symptoms like shortness of breath and unrefreshing sleep. Now, with a better understanding of long-COVID, we’re breaking that pattern, and that is good. Long COVID is too widespread to ignore.

Objective measurements of PAISes will not only lead to improved diagnosis and the development of evidence-based treatments, but also protect patients from grifters who’ve created entire industries preying on the sick who are desperate for answers and who, feeling like they have no other choice, can be separated from their money with the promise of relief. Take, for example, Envita, the "Cancer and Lyme disease treatment specialists” in Arizona, where we don’t have endemic Lyme disease. They offer treatments like “Next-level Detoxing!” Great, because the first few levels weren’t doing it for me. Bogus “healers” drive me absolutely bats, because they’re not just scamming money from desperate people, but often providing “therapies” that can cause real harm.

I don’t fault patients for being willing to do anything to feel better, but new research into long-COVID might soon allow us to say “I believe you. I don’t know what’s wrong. We’re working on it. Those other guys don’t know what’s wrong either, even if they’re charging 10k.”

Multiple studies demonstrate that women’s pain is more frequently dismissed as psychosomatic in origin, and not only dismissed when symptoms are “vague.” For example, one paper (among many) from the Journal of Women’s health found that, in patients presenting with chest pain, middle-aged women were most likely to receive a mental health condition as the “most certain diagnosis” compared to male counterparts, who were more likely to receive a “most certain diagnosis” of cardiac origin. Just as women’s physiologic complaints are more likely to be dismissed as “in their head,” men’s mental health manifestations are assumed to be externalizing—violence, substance abuse—and psychosomatic symptoms, depression and anxiety with internalizing factors are often dismissed.

Dismissing women’s medical complaints as “made-up,” “hysterical,” or “caused by wandering uterus”, has been in fashion for centuries, if not longer. The lack of mechanism and objective biomarkers for illnesses such as ME / CFS means there’s no good way to confirm a diagnosis or develop and then adequately monitor treatments, furthering the bias that these syndromes are largely psychosomatic. But, as my childhood crush Dr. Carl Sagan used to say, “Absence of evidence doesn’t mean evidence of absence.

The lack of a diagnostic biomarker, combined with the prevalence in female patients, might explain why, according to the CDC, in 2018 less than one-third of US medical schools taught about ME/CFS, and the NIH spent only $15 million (very little in research dollars) on research. As an alternate explanation, researchers might feel they don’t have a good way to attack these kinds of problems right now. Long-COVID research is changing that.

It's possible that the higher prevalence of PAIS in women occurs because women’s immune systems are more vulnerable to pathogenic triggers in the same way that autoimmune diseases are more prevalent due to a second X chromosome. But that’s only my speculation.

None of this is to say that there aren’t psychosomatic disorders. It’s also true that stress, inactivity, diet, and other factors can cause symptoms similar to long-COVID and other PAISes. Reducing stress, increasing activity, improving nutrition, getting enough sleep, and the usual things that we all know we should do, but often don’t, improve health.

With those caveats/qualifications, finding objective blood biomarkers for PAISes may finally legitimize and destigmatize what have largely been dismissed as “women’s complaints.” Interferon-Gamma, an immune cytokine produced by T cells in the defense against viral infections, that plays a may be one such biomarker.2

Is there a scientific foundation for thinking that the mechanisms underlying long-COVID might be shared by other PAISes?

In short:

· An NIH project evaluating ME/CFS with matched controls demonstrated signs of persistent chronic antigen stimulation, T-cell dysregulation, and decreased cardiovascular performance in ME/CFS diagnoses, compared to a control group. What’s that mean? Chronic antigen stimulation and T-cell dysregulation happens when the immune system is overstimulated by an ongoing infection, causing the immune system to either become exhausted or overly aggressive: this can lead to a depressed immune system and increased susceptibility to other infections or autoimmune responses. Decreased cardiovascular performance occurs when there’s a reduction in the effectiveness of the heart and blood vessels to circulate blood, which leads to decreased endurance and difficulty breathing when trying to exercise. This also happens to patients with Epstein-Barr-Virus (defective T-cell control in patients with EBV, the virus that causes mono, may lead to the development of MS).

· A paper in Nature Neuroscience hypothesizes that the “brain fog” symptoms of CFS/ME might be secondary to a dysfunctional blood brain barrier, which “implies initial systemic inflammation caused by a viral/bacterial infection.” This means the normally very tight control over what can move from the bloodstream into the brain becomes disrupted. Something similar happens from watching too much reality t.v. Think of it like that time you won a goldfish from the fair as a kid and the bag started off okay, but then started to break down and sprung a few leaks so that, eventually, all the water came out and the fish met a bad end. A leaky blood brain barrier is like that, but in reverse, letting dirt and debris into the bag. A recent paper implicates a leaky blood-brain barrier as the mechanism for brain-fog symptoms in long COVID as well. I might have been too hasty before, saying we’re wrong to over-diagnose fatigue syndromes as being “all in your head.” Since there’s a leaky blood brain barrier, it turns out, a lot of it is all in your head. Just… not in the way it's usually meant. (hat tip to Eric Topol for this study.)

· Microbiome dysbiosis—an imbalance in the microbial communities in the digestive tract. Feeling farty (that’s the medical term)? Feeling farty might not be from irritation at spending time with your in-laws, but rather it might be from an overgrowth of the wrong intestinal bacteria. It’s a finding present in long-COVID patients, as well as other infections, such as Helicobacter (Like H. Pylori, the bacteria that can trigger stomach ulcer formation) and Streptococcus. There’s even a theory that certain infections, like Enterovirus, cause gut dysbiosis which leads to the development of type 1 diabetes, which would be one of the more serious PAISes.

· Endothelial inflammation, when the lining of blood vessels becomes inflamed, is implicated in long COVID symptoms. Inflamed blood vessels can cause the blood to clot and create multiple tiny blood clots throughout the body. Similar endothelial dysfunction is also well documented in dengue fever, Hantavirus, HIV and influenza.

· Viral persistence, or viruses that remain in the body for much longer than the average infection (or permanently) cause a prolonged, persistent immune response that leads to PAISes. Some COVID patients are found to have viral persistence for many weeks, or months, and they’re at increased risk for long-COVID. 95% of adults carry EBV, and viruses like Herpesvirus and Chickenpox reside inside your affected nerves forever, rearing as cold sores or shingles respectively.

Now that long COVID is affecting millions of people and there’s social pressure for accelerated research and drug development, I can imagine a future in which a multiple drugs targeting the various underlying mechanisms of long-COVID are successfully developed. Then, blood biomarkers from patients with long-COVID could be compared to biomarkers in patients with other PAISes. If there is an overlap in the long-COVID biomarker and the PAIS biomarker, it’d be safe to guess there’s a similar underlying mechanism causing the patient’s chronic symptoms. Drugs treating that mechanism in long-COVID patients could then be trialed in patients with other PAISes. . Basically, we could clump treatments together based on biomarkers and mechanism instead of inciting pathogen. Neat!

One snag: Pathogenic persistence.

But what if the pathogen does more than just trigger a persistent downstream effect even after it’s gone? What if it isn’t gone, much like the alien creatures in the Alien and Aliens films tend to be killed, then come back and stick their pointy appendages into more crew members on the Weyland-Yutani spacecraft USCSS Nostromo? In this case, the focus would have to be pathogen-specific.

We know that, for some viruses and bacteria, the cost of persistent infections is extremely high:

· Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) infections are implicated in cervical, anal, oral and genital cancers.

· Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) is a major risk factor in the development of multiple sclerosis (30-fold increase in risk), lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal cancer. And maybe other things!

· Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) may play a major role in Alzheimer’s.

· Lyme disease is theorized to hide out in the lining of blood vessels. It’s unclear whether antibiotics resolve this, or if symptoms of “Long Lyme” are actually secondary to a persistent infection, but spirochetes, the type of corkscrew bacteria that causes Lyme disease, are weird. Syphilis is a different kind of spirochete and it’s really weird and horrible in a myriad of often gross and deadly ways. Luckily, we figured out syphilis with a few large shots of penicillin in the behind. Fortunately, too, a bunch of syphilis vaccine candidates are in the pipeline, too.

We’re reasonably good at wiping out bacteria through antibiotics (although bacterial resistance is making this harder), but we’re not good at antivirals. We have some antiviral drugs that mostly don’t work well. Xofluza and Tamiflu, for example, exist, but I wouldn’t call “reducing the duration of influenza by 24 hours” a massive public health coup. Paxlovid decreases COVID viral replication but comes with its own slew of problems, and rebound suggests it’s not terribly viricidal. Valtrex reduces viral replication of herpes, but herpes remains, at current levels of medical science, in your affected nerves forever. HIV and HIV antivirals suppress, but don’t cure, infections.

To address viral persistence, vaccines, especially mRNA vaccines, are our best bet for speed and flexibility, primarily by preventing infection in the first place or reducing viral load upon infection, which might not fully prevent persistence, but could reduce the risk of PAISes. Variolation, or the amount of virus a person is infected with, can matter a great deal in terms of severity and long-term symptoms. mRNA vaccines are great because they’re faster, cheaper and more flexible than their traditional vaccine counterparts. Who doesn’t love fast, cheap, and flexible?

MRNA vaccines also don’t rely on growing large quantities of weakened virus or viral vectors, so there’s no reason to be concerned that they could cause an infection, even in a person with a severely weakened immune system. MRNA doesn’t require cell cultures to produce. It’s a fully cell-independent process. Synthetic mRNA, the foundation of mRNA vaccines, can be designed and manufactured in a lab within days, meaning reformulations in the event of mutations are easy to make and rapidly deploy.

MRNA vaccines are great: They’re not only giving us a speedy way to fight pathogens, but a path towards curing cancer, as well. My husband, Jake, is dying from metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and the current standard of care treatment options are to basically suffer for a short time, then die. A clincal trial is currently keeping him alive with less suffering than chemo, but , Moderna’s mRNA-4157 personalized cancer vaccine is his best shot for some kind of durable response.

Not surprisingly, part II is about mRNA vaccines. Look for it in a couple days!

If you’ve gotten this far, consider the Go Fund Me that’s funding my husband Jake’s ongoing cancer treatment.

Everything Is An Emergency is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. I love knowing if you’ve enjoyed an essay: feel free to click that heart button, leave a comment, and share with friends!

I’m deliberately defining the acronym twice, because “CFS / ME” is easily forgotten amid all the other action in this essay.

Interferon-Gamma was elevated in all patients with acute covid, but decreased in patient whose symptoms resolved. In long-COVID patients, levels remained elevated.

I just found you here, doc, and I will link to your newsletter in my own (which covers LC, ME/CFS, and other health conditions, with info and humor). Thank you for such thorough treatment of the available info on causes/treatments and history too.

I just wanted to point this out:

“I don’t fault patients for being willing to do anything to feel better, but new research into long-COVID might soon allow us to say “I believe you. I don’t know what’s wrong. We’re working on it.”

I urge docs not to wait for the research to utter these words. There’s no reason to wait to validate patients with these symptoms. After being gaslit by docs for the first half of 2020 around my persistent symptoms after COVID, the second half of 2020 had me finding docs who used the above language with me and it did wonders for helping me feel heard and understood. If some docs who could put ego and rigid medical dogma aside in 2020 could utter these words, every single doctor should be able to say them in 2024, given just how much research has already emerged.

As a long covid sufferer, thanks for this well laid out article!